Lincoln Avenger, Thomas P. Corbett, was not only the man responsible for killing Lincoln’s assassin, but would be forever remembered as Boston, the Mad Hatter! The details of Lincoln’s assassination, the cast of clowns that participated in the conspiracy, man-hunt, killing of the assassin, military trial and rush to judgement, could only be characterized as an event in American history, that is blurred by nearly 150 years of literary memory or when taken in the whole, might be one of the most farcical and tragic tales of the genesis of the civil strife that divided the United States in the 19th century.

Lincoln Avenger, Thomas P. Corbett, was not only the man responsible for killing Lincoln’s assassin, but would be forever remembered as Boston, the Mad Hatter! The details of Lincoln’s assassination, the cast of clowns that participated in the conspiracy, man-hunt, killing of the assassin, military trial and rush to judgement, could only be characterized as an event in American history, that is blurred by nearly 150 years of literary memory or when taken in the whole, might be one of the most farcical and tragic tales of the genesis of the civil strife that divided the United States in the 19th century.

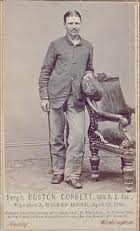

Thomas P. Corbett, was born in London, England in 1832 and his parents immigrated to New York City when Thomas was 7 years old. They settled in Troy, New York, in 1839, where he learned the hat trade, soon becoming a journeyman and taking his skills to other cities around the East. The beaver hats then so much in style were made of animal furs matted and repeatedly washed in a solution containing mercury nitrate, a process called carroting, because it turned the fur a distinct shade of orange. Hat finishers like Corbett labored in close quarters, inhaling vapors laden with mercury. There is a theory that the mercury used in the hatter’s trade may have caused some of the Corbett’s mental problems as he aged. Some of the symptoms associated with mercury poisoning include irritability, exaggerated responses to stimulation, emotional instability, and fits of anger with violent often irrational behavior. Thomas soon married and his young wife died in child-birth with their stillborn daughter.

Unhinged, he moved to Boston, in 1858 and began drinking heavily. One night the drunken hatter encountered a street preacher whose message apparently filtered into his befuddled brain, instantly transforming him into a religious zealot. But so extreme was his conversion, so loud, incoherent and vehement his exhortations to others, that he embarrassed his fellow-evangelists. Corbett was equally embarrassing to any hat-makers who gave him jobs. Let a fellow-workman mention taking a drink, or utter some careless oath, and Corbett would disrupt the assembly line, get on his knees, and make a long and fervent prayer. Corbett felt that he should commemorate the city of his conversion, so he abandoned the “Thomas P.” and took the name “Boston” and grew his hair long, in imitation of Jesus. Thomas took the Gospel literally, one passage from Mathew Chapter 18 changed Corbett’s life forever,

“If your hand or your foot causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away. It is better for you to enter life maimed or crippled than to have two hands or two feet and be thrown into eternal fire. And if your eye causes you to sin, gouge it out and throw it away. It is better for you to enter life with one eye, than to have two eyes and be thrown into the fire of hell.”

When the 26-year-old Corbett was mocked and tempted by local prostitutes, he took out a pair of scissors and castrated himself. After performing the operation, Corbett then went to a prayer meeting, ate a hearty meal and then walked awhile before seeking medical attention. Boston Corbett’s medical records from Massachusetts General Hospital indicate Corbett was hospitalized from July 16 through Aug. 15, 1858, where he recovered from his self-imposed injury. In his own mind, he had done as the Bible said: he had made himself a eunuch “for the kingdom of heaven’s sake.” He said years later that he felt divinely instructed; he wanted to “preach the gospel without being tormented by animal passions.” The grisly experience may have removed him from sexual temptation, but the rest of his life proved to be full of incredible experiences and tales of daring and survival.

After weeks recovering, he moved to New York and became a loud and constant presence at the Fulton Street Meeting, a lunchtime prayer gathering in lower Manhattan organized by the Young Men’s Christian Association. He was too fervent for his co-worshipers, who called him a fanatic. When he testified or led prayers, he added an emphatic “er” to his words, saying “Lord-er hear-er our prayer-er.” In his loud shrill voice, he shouted “Amen” and “Glory to God!” to approve anything he liked. Those around him tried to hush him, but failed.

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Corbett enlisted in the 12th New York Volunteers two days before the regiment sailed for Washington. He was eager to get at the Rebels: “I will say to them, ‘God have mercy on your souls’—then pop them off.” Morning and night, he prayed in the corner of his tent, despite the jeers of his fellow troopers. His resistance to military authority, to any authority below that of Christ, got him into the guardhouse and sometimes had him marching back and forth with a knapsack full of bricks. Even then he kept his Bible in hand, ranting at his comrades for their sins.

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Corbett enlisted in the 12th New York Volunteers two days before the regiment sailed for Washington. He was eager to get at the Rebels: “I will say to them, ‘God have mercy on your souls’—then pop them off.” Morning and night, he prayed in the corner of his tent, despite the jeers of his fellow troopers. His resistance to military authority, to any authority below that of Christ, got him into the guardhouse and sometimes had him marching back and forth with a knapsack full of bricks. Even then he kept his Bible in hand, ranting at his comrades for their sins.

He was not afraid of the highest brass; in parade formation in Washington’s Franklin Square, when colonel and future general Daniel Butterfield cursed the regiment for misbehavior, Corbett stepped forth and defied him to his face. He announced that he would quit the army when his first hitch was up, no matter what. When the hour came, he was on picket duty, but laid down his weapon and marched off. A court-martial fined him two months’ pay, yet he kept re-enlisting.

The 12th New York Volunteers were among the 12,500 Union troops captured, then paroled by Stonewall Jackson’s Confederates at Harper’s Ferry, just before the battle of Antietam in September 1862. The following year, Corbett switched to Company L of the 16th New York Cavalry, a regiment that spent much of its time chasing John Mosby’s Confederate raiders on the outskirts of Washington. That June, Mosby’s raiders surprised Corbett and a detachment from Company L who were looking for them near Centreville. Official records say the Union troopers were loafing about after a meal and unprepared when the Rebels struck; Corbett’s version was: “I faced and fought against a whole column of them, all alone, none but God being with me, to help me, my being in a large field and they being in the road.”

The 12th New York Volunteers were among the 12,500 Union troops captured, then paroled by Stonewall Jackson’s Confederates at Harper’s Ferry, just before the battle of Antietam in September 1862. The following year, Corbett switched to Company L of the 16th New York Cavalry, a regiment that spent much of its time chasing John Mosby’s Confederate raiders on the outskirts of Washington. That June, Mosby’s raiders surprised Corbett and a detachment from Company L who were looking for them near Centreville. Official records say the Union troopers were loafing about after a meal and unprepared when the Rebels struck; Corbett’s version was: “I faced and fought against a whole column of them, all alone, none but God being with me, to help me, my being in a large field and they being in the road.”

Harper’s Weekly would make him a hero, reporting that the Yankee cavalrymen “were hemmed in . . . and nearly all compelled to surrender except Corbett, who stood out manfully, and fired his revolver and 12 shots from his breech-loading rifle before surrendering, which he did after firing his last round of ammunition. Mosby, in admiration of the bravery displayed by Corbett, ordered his men not to shoot him, and received his surrender with other expressions of admiration.” Corbett was imprisoned for five months in Andersonville and when he was released he was emaciated, suffered from scurvy, diarrhea and fever. After spending three weeks in an Annapolis hospital recovering, he rejoined his regiment in Virginia.

On April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth shot President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre. The next day Corbett was selected with 26 other cavalrymen to pursue Booth. On April 26, 1865, the soldiers cornered Booth in a Virginia tobacco barn. Federal officials wanted to take Booth to court. A fire was set to the barn to flush Booth out. But as the president’s assassin moved inside the barn, a shot rang out and as the barn doors were opened, the soldiers found Booth dying of a wound to the neck. Corbett claimed to have shot Booth through a crack in the barn boards, although people at the scene said it couldn’t have been him. Corbett said he had seen Booth raise his pistol, and shot. Corbett was charged with disobeying orders but freed by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton who was quoted as saying, “The rebel is dead. The patriot lives.”

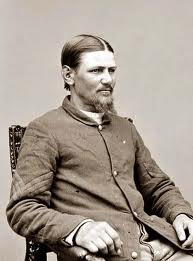

Corbett would later say, “Providence directed my hand.” And the nation’s media turned him into a hero. He was photographed by famed Civil War photographer Mathew Brady. He received more than $1,600 in reward money but then immediately was discharged from the Army. Boston Corbett would testify at the Lincoln Assassination military trial of the conspirators and also the Henry Wirz Andersonville trial.

Boston Corbett started making hats again after mustering out, but his mental problems apparently worsened. Quick to anger and increasingly paranoid, he now slept with a loaded pistol under his pillow. It was said he feared assassination from Confederate veterans seeking revenge for John Wilkes Booth. In 1878, Corbett traveled to Cloud County, Kansas, and homesteaded 80 acres on seemingly worthless land 18 miles southeast of Concordia. He built himself a sod and stone dugout, with holes in the walls so he could fire out at interlopers. He lived as a recluse, wandering the countryside on his cherished little black horse Billy.

Boston Corbett started making hats again after mustering out, but his mental problems apparently worsened. Quick to anger and increasingly paranoid, he now slept with a loaded pistol under his pillow. It was said he feared assassination from Confederate veterans seeking revenge for John Wilkes Booth. In 1878, Corbett traveled to Cloud County, Kansas, and homesteaded 80 acres on seemingly worthless land 18 miles southeast of Concordia. He built himself a sod and stone dugout, with holes in the walls so he could fire out at interlopers. He lived as a recluse, wandering the countryside on his cherished little black horse Billy.

What would be known as the “baseball incident” took place on a Sunday morning, when some local boys were playing baseball. Reading scripture while driving past in his buckboard, Corbett became incensed that his neighbors were indulging in what he saw as a “profane” game on the Sabbath. Stopping his horse, he took a pistol from his belt and shouted, “It’s wicked to play baseball on the Lord’s Day!” brandishing his weapon. The frightened youngsters and bystanders quickly scattered.

The next day a warrant was sworn out for Corbett, who was summoned to appear in the office of Concordia’s Justice of the Peace to stand trial. Corbett showed up fully armed at the trial, placid at first, but eventually stated, “I’ll shoot any man who says anything against me!” Somehow the officials managed to calm Corbett, who left the office unmolested. All thought of further legal action against the former hatter was shelved. The Kansans realized he was not exactly normal, and was perhaps even insane—but still felt great sympathy for him.

After the baseball incident, a local politician managed to get Corbett a job as a doorkeeper in the Kansas State Legislature at Topeka. For a month all went well; Corbett stuck to his duties and became something of a tourist attraction. But the hatter once again went off the rails on February 15, 1887. Corbett started running around the capitol corridors raving, waving a revolver as the legislators ran for cover. After officials subdued and examined him, he was sent to the Kansas State Insane Asylum.

On May 26, 1888, while Corbett and others were outside exercising, the wily former cavalryman spotted a horse tethered nearby and when the Asylum attendant was momentarily distracted, Corbett galloped away. A few days later, a letter came saying the horse could be reclaimed at Neodesha, Kansas, 75 miles south. Corbett had spent two nights there with an old soldier who had suffered with him at Andersonville. He borrowed train fare and then departed, saying he was headed for Mexico. Rather than going to Mexico, Corbett is believed to have settled in a cabin he built in the forests near Hinckley, in Pine County in eastern Minnesota. He is believed to have died in the Great Hinckley Fire of September 1, 1894.

Whether Lincoln Avenger or Boston Mad Hatter, Thomas P. “Boston” Corbett was a character whose exploits, no matter how strange or far-fetched, could not have been fabricated by any sane academic or historian, a tale of the American Civil War and its bigger than life participants.

Bummer

Thanks for filling in the rest of Corbett’s story; until now everything I’ve read about him ends with the incident at the Kansas statehouse. Also was not aware before that he probably didn’t shoot Booth – is it certain who did? It couldn’t have been suicide from the location of the wound. Corbett sounds like the soulmate Jack Ruby never knew he had – two guys with loose (at best) grips on reality who insisted on inserting themselves into important moments in history.

Louis,

The rest of the story is fairly muddled with Corbett. His name is listed among the dead in the fire in Hinckley. But, numerous reports of sightings were mentioned all over the country, some using aliases. Several different persons, including two detectives at the scene, employed by Stanton, tried to claim a portion of the $75,000 reward. Boston was such an odd duck, it was just hard for folks to believe that he could be the hero. Stanton gave explicit orders that Booth was to be taken alive and after the deed, he initially had Corbett jailed. Public opinion and the media forced Stanton to release Boston and proclaim him a Union hero and an Avenging Angel. Corbett recieved a little over $1600 and the rest went to the detectives and officers of the detachment.

Bummer

i had been told stories as a child that the corbett family/grahams of ohio were 2nd cousins to booth. through the xampbell family of long island.